How to republish

Read the original article and consult terms of republication.

Air pollution: effective but imbalanced low-emission zones in France

By Alexis Poulhès et Laurent Proulhac, Laboratoire Ville Mobilité Transport (LVMT), École des Ponts ParisTech, Université Gustave Eiffel

Multiple studies have warned of the impact of air pollution on human health, but the public authorities do not seem to have grasped the scale of the problem.

In 2015, the city of Paris decided to introduce France's first low-emission zone (LEZ). At the urging of the European Union, the French government subsequently finally introduced LEZ-s in other French cities, following in the footsteps of its neighbours.

In 2023, just 11 cities have LEZs, but by 2025, 43 will have them thanks to the French Climate and Resilience Act, which has made their introduction compulsory.

The aim is to reduce the impact of car pollution by gradually restricting access to cities for the most polluting vehicles, as defined by the Crit’Air scheme which categorises vehicles according to their engine type and age.

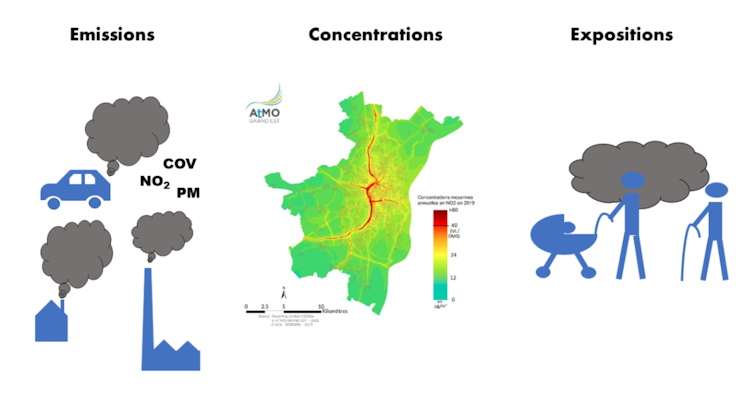

The approach targets two of the most prevalent pollutants in cities with the greatest impact on human health: nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and fine particulate matter (PM).

LEZs and pollutants

In the 1990s, Europe introduced the Euro standards to limit pollutant emissions from road vehicles. In 20 years between Euro 0 and Euro 6, nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions have been cut by a factor of 20.

However, the Dieselgate scandal in 2015 highlighted biases in emissions measurements and it was not until 2016 that these measurements were finally calculated using a test that reflected real driving conditions.

The European Union is currently trying to introduce a Euro 7 standard that will also limit PM released by tyres and brakes, which account for the majority of particles emitted by the most recent vehicles.

Initial results

In Ile-de-France, Airparif has estimated the benefits of accelerating the renewal of the road vehicle fleet through the LEZs.

If the measure is strictly complied with, an improvement of 3 to 20% can be expected for PM emissions, depending on the area. However, the benefits are not limited to LEZs through the reduction of pollutants released into the air, but also concern the renewal of the vehicle fleet of residents outside the LEZ who have to change car in order to enter the area.

Air quality is often viewed through the prism of pollutant concentrations in the air, which has the advantage of reflecting the multifarious pollutant sources and of being spatialised. While NO₂ in the air in cities comes mainly from road traffic, this is not the case for PM, which has been steadily decreasing in recent years. The main source of PM is building heating systems, particularly wood-burning systems, even in large cities where its use is partially regulated (only authorised for domestic use in Paris and Lyon, but still strangely allowed).

At the European level, feedback from LEZs in which restrictions only apply to the oldest vehicles show that concentrations of NO₂ and PM are only reduced by a few percent.

A strong potential impact on health

To minimise the impact of air pollution on health, epidemiologists have defined exposure levels that should not be exceeded for more than a certain time during the year. These levels are not only based on where people live, but also on where they carry out their daily activities.

This is why LEZs benefit residents within the zone itself, but also those who live outside the zone and enter it for part of the day.

However, if the results are to live up to expectations, the acceptability of such schemes must be promoted within societies and checks must be introduced for vehicles circulating within the zone, which currently seems too risky from a social point of view.

Pollution causes unequal levels of damage

LEZs highlight the tensions between the environmental and social challenges of regulating transport and travel.

Residents in city centres generally suffer more from PM and NO2 air pollution, but are less likely to use a car on a daily basis.

These area-based inequalities are underlined by the fact that a proportion of motorists from the outskirts emit pollutants in the centre but suffer no effects of this pollution in the area where they live.

As they are currently defined, LEZs partially address this inequality by restricting access for some of the most polluting vehicles.

LEZs penalise the least wealthy

The downside is that the vast majority of cars targeted by the measure are owned by residents in the lower echelons of society, who struggle to afford a new car despite the support available.

This structural social inequality is exacerbated by the new legitimacy of recent vehicles, the heaviest of which are among the most expensive and best-selling, such as SUVs. However, like long-range electric cars, they contribute significantly to PM emissions.

What is more, cars are sometimes more essential for people in the most modest social categories, who often live far from the centre, work shifts and have poor public transport links.

An alternative system could focus on the weight of cars to target the wealthier residents in city centres who still own vehicles and, even with the LEZ, retain a form of transport that is poorly adapted to the very dense urban environment.

Very costly switchover support

Whatever the vehicle, even if successive engine standards reduce emissions, the gains from fleet renewal are faced with a major obstacle.

Financial support for buying an electric SUV is very expensive for the government and has limited environmental benefits. Like for many urban nuisances, solutions lie in reducing car traffic and revolutionising urban development on the outskirts of cities.

However, decades of car-friendly transport and urban planning policies are now hindering policies to restrict car use in the suburbs.

Rethinking peripheral urban development

There is an urgent need to reduce the use of cars and promote walking and cycling, and this must no longer be limited to city centres alone. The ongoing urban sprawl continues to produce car-dependent peripheral areas.

Links between the city centre and its outskirts require coherent policies to be put in place in order to avoid contradictory approaches between car-restricted centres and an increasing urban sprawl composed of housing estates, giant logistics warehouses and shopping areas.

Air pollution must not be seen as a localised problem requiring a sectoral response. It touches on issues ranging from noise and accessibility to social justice and planetary boundaries. All these issues need to be considered in a global and systemic way if the responses are to be fair and effective.

![]()

Identity card of the article

| Original title: | Pollution de l'air : En France, des zones à faibles émissions efficaces mais inégalitaires ? |

| Authors: | Alexis Poulhès et Laurent Proulhac, Université Gustave Eiffel |

| Publisher: | The Conversation France |

| Collection: | The Conversation France |

| License: | This article is republished from The Conversation France under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. An English version was created by Hancock & Hutton for Université Gustave Eiffel and was published by Reflexscience under the same license. |

| Date: | June 27th, 2023 |

| Langages: | French and english |

| Keywords: | Air pollution, urban planning, electric cars, travel, reducing emissions low emission zone |

![[Translate to English:] Licence creative commons BY-SA 4.0 [Translate to English:] Licence creative commons BY-SA 4.0](https://reflexscience.univ-gustave-eiffel.fr/fileadmin/ReflexScience/Accueil/Logos/CCbySA.png)