How to republish

Read the’original article and consult terms of republication.

Mobility: another inequality suffered by working class areas

By Thibault Isambourg, Transdev, ENTPE, Université Gustave Eiffel

The Wikipedia article on « Riots in French suburbs since the 1970s » recently grew with the addition of the cycle of violence that spread across the country in late June and early July 2023. The problem is a complex one with a range of causes that differ depending on urban contexts and individual situations. Generally speaking, this type of event is the out-pouring of a deep-seated malaise..

It is easy to see why. Working class districts are faced with inequalities in several areas: resisdents are in poorer health and have access to fewer healthcare services ; in terms of education, school results are lower (particularly at the age of aroude 14-15), and aspirations for upward social advancement are curtailed. These difficulties are aggravated by the fact that teachers are less experienced than elsewhere in France.

Everyday mobility is no exception and the “travel enclave” problem is often brought to the table by politicians. French urban policy aims to reduce inequalities and has increasingly addressed the problem of transport (e.g. the Dijon Pact en 2018). This policy is based on the definition of geographical areas called urban policy development areas (QPV), formerly known as sensitive urban areas (ZUS). Directives are set at national level.

However, urban policy is currently informed by fragmented studies carried out at local level and on received ideas – which are plentiful with regards to working class districts! To our knowledge at the time of writing, no studies have been carried out on mobility in QPV that are representative of France as a whole.

We have therefore sought to objectivise some of the characteristics of mobility in these deprived areas on a scale that is representative of the whole country. Using the two most recent national mobility surveys (2019 and 2008), our study, compared surveys based on area-specific urban policy (QPV or ZUS) with others. The results showed the existence of inequalities.

They also showed that the “travel enclaves” in working class areas are caused by a range of factors, requiring public authorities to take action on several fronts.

Forced limitations

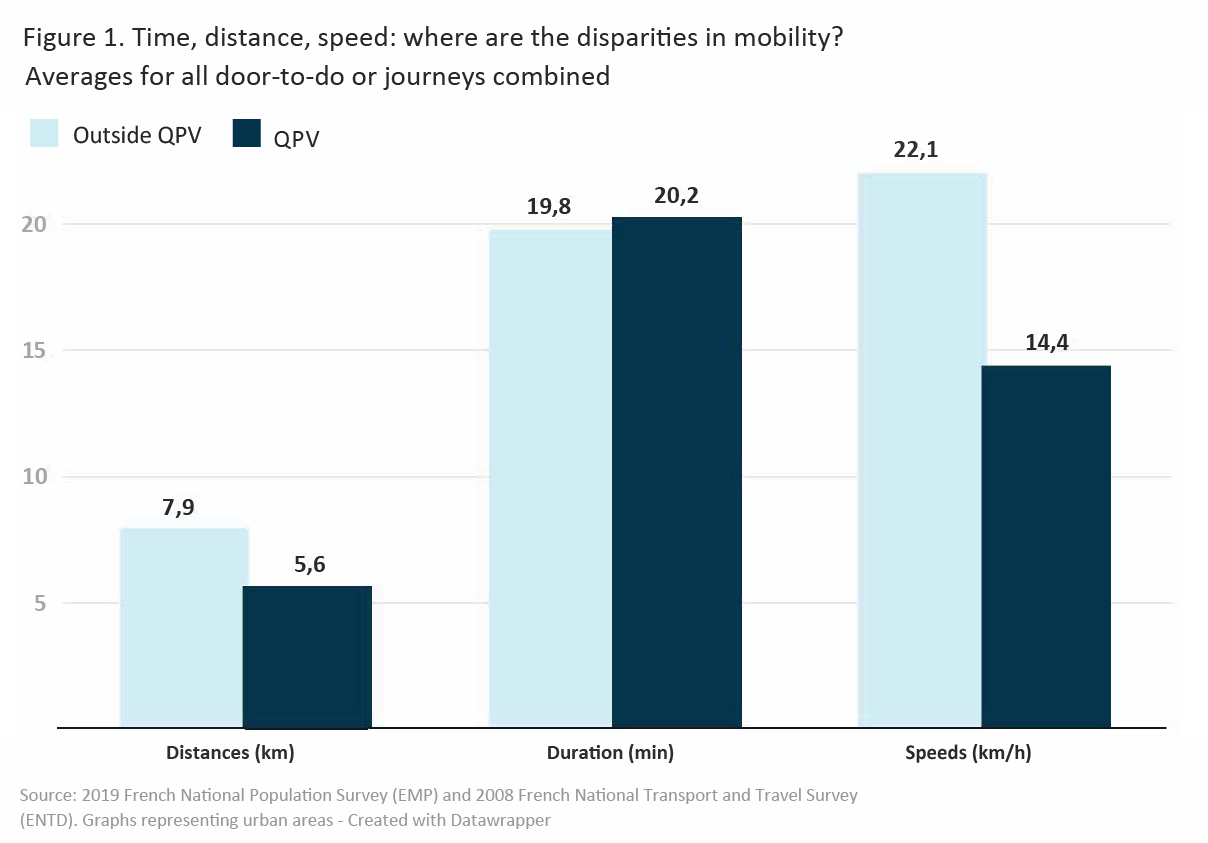

The average door-to-door journey time for all urban commuters is approximately 20 minutes. However, there are significant differences in the distances travelled, which reflect local urban mobility and are considerably shorter in deprived areas. This is caused by unequal access to speed, particularly the fastest means of transport. In this sample, the average door-to-door speed was 22 km/h, but was one third slower working class districts.

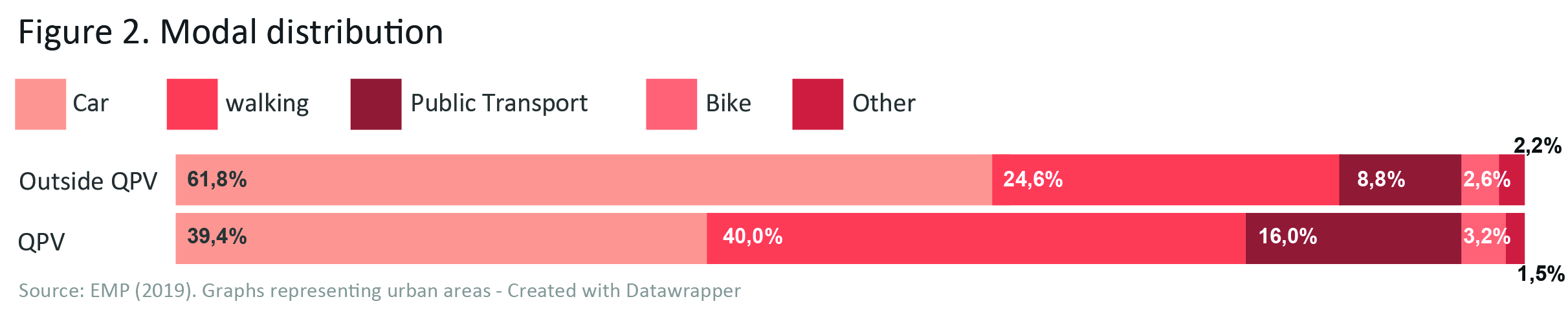

This trend is due to the much less intensive use of the most efficient mode, i.e. cars (including in large urban areas such as Lyon). Cars are used for more than 6 out of 10 journeys in urban areas, compared with fewer than 4 out of 10 in development areas, where more people use low-impact modes of transport, such as walking and public transport.

These disparities were already apparent in 2008 and grew by 2019.

Multiple limitations

Studies carried out in cities highlight inequalities in car ownership as the main factor explaining mobility disparities. Likewise, car ownership in our sample varies significantly.

However, certain characteristics of deprived areas could skew interpretation. For example, the population in these areas is younger, unemployment is higher and more residents live in built-up areas. These factors are known to increase the likelihood of using active modes of travel and public transport.

To clarify the influence of each of these factors on people's choices, we developed a statistical model to neutralise the biases inherent in studying working class districts.

The results obtained using this model were very clear. Firstly, there are major inequalities in vehicle ownership in working class neighbourhoods. Secondly, these inequalities account for a significant proportion of the differences in “choice” of mode of transport, although they are far from being the only factor explaining variations in mobility.

In reality, the “transport enclave” facing the inhabitants of working class neighbourhoods is not simply a question of distance, but of a system of constraints. In addition to individual factors (economic insecurity, sociocultural diversity, digital divide, etc.), the urban environment also has a strong impact on mobility. The causes include major inequalities in access to the city's resources, particularly employment. Isolation caused by the major infrastructures that subdivide cities also plays a role, as does the fact that streets have fewer facilities and higher accident rates.

Will new urban contracts resolve the problem?

There is still work to be done to reduce inequalities in working class districts in France. The proposals made so far by President Macron, such as reconstruction work after the damage caused by riots and the attempt to establish a «minimum charge for the first offence», do not address the root of the problem.

The new urban contracts, due to be introduced in early 2024, are an opportunity for public authorities to propose an ambitious response after the rejection of the Borloo Plan in 2018.

It is important for these contracts to be linked to mobility and sustainable city policies. Our research highlighted the fact that residents in deprived areas travel less far but are one step ahead in terms of moderating consumption. However, this moderation is not so much a matter of choice as of necessity.

It also risks being exacerbated by the combination of rising energy prices and regulatory requirements. For example, the current generalisation of Mobility Low-Emission Zones (ZFE-m) excludes part of the urban population who own older vehicles (generally lower-income households).

In-depth knowledge of the constraints facing these neighbourhoods is required in order to inform urban policy. Based on a participatory approach, the “citizen participation in neighbourhoods” commission formed by the minister for cities and housing, could provide solutions that come directly from the inhabitants’ perspective.

It is also essential to increase scientific input in all areas in which inequality is a threat (education, healthcare, housing, employment, safety, etc.). In terms of mobility, it is important to support area-specific knowledge and, above all, break free from the idea of a uniquely physical «travel enclave» in order to build effective solutions.

We could consider, for example, how best to adapt public transport services for residents who are less likely to own a vehicle and are employed in less-qualified jobs. One example is logistics, a sector that recruits many urban workers but in which companies are often located on the edge of cities, and are less accessible via public transport particularly at unusual hours of the day, yet shift work in this field is more common. The possibilities for concrete action are varied and need further assessment.

Identity card of the article

| Original title: | La mobilité, l'autre inégalité subie par les quartiers populaires |

| Author: | Thibault Isambourg |

| Publisher: | The Conversation France |

| Collection: | The Conversation France |

| License: | This article is republished from The Conversation France under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. An English version was created by Hancock & Hutton for Université Gustave Eiffel and was published by Reflexscience under the same license. |

| Date: | March 9th, 2024 |

| Langages: | French and english |

| Keywords: | inequalities, motor vehicles, suburbs, mobility, urban policy, working class neighbourhoods, riots |

![[Translate to English:] Licence creative commons BY-SA 4.0 [Translate to English:] Licence creative commons BY-SA 4.0](https://reflexscience.univ-gustave-eiffel.fr/fileadmin/ReflexScience/Accueil/Logos/CCbySA.png)