How to republish

Read the original article and consult terms of republication.

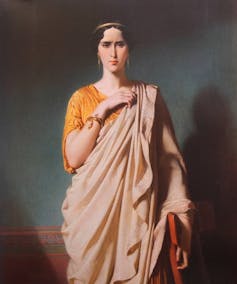

Sarah Bernhardt: an actress who imposed her gender

This year’s exhibition by the Petit Palais devoted to the eclectic actress Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923) to mark the centenary of her death, was a masterful demonstration that to be an actress means knowing how to be “the other”, to play with multiple, sometimes contradictory identities.

Sarah Bernhardt, whose acting and personality turned the world of theatre upside down, and for whom Jean Cocteau coined the expression “sacred monster”, recounts and analyses her ability to change skin, one acquired not without suffering, her power of metamorphosis and the exhilarating freedom it offers in her expressively titled autobiography Ma double vie (1907) and in what she saw as her theatrical testament L'Art du théâtre : la voix, le geste, la prononciation (1923, posth.). Following her death, novelist Marcel Berger, a close friend of hers, collected and organised the scattered texts she had dictated or written on the subject.

Special attention to the status of women

As she recounts her life, Sarah Bernhardt pays special attention to the difficulties faced by women. Her childhood and adolescence undoubtedly had something to do with this. At the age of seven, she was sent to Madame Fressard’s boarding school in Auteuil, and two years later she went to the Grand-Champs convent in Versailles. At the convent, she developed a boundless admiration for the Mother Superior, Saint Sophie, and a spirit of female camaraderie that would follow her throughout her life.

As she recounts her youth, we are struck by the delightfully beautiful portraits of women she describes, which later underpin her autobiography. As the chapters go by, she pays heartfelt tribute to the women who were important in her life, without idealising them, like her dear old teacher Mademoiselle de Brabender, of whom she even includes a description on her deathbed, her face deformed by the removal of her dentures, deposited in a glass.

Often full of tenderness and admiration, these portraits are no less realistic than they are the mark of sincere affection: she did not shy away from the prosaic nature of the characters and bodies she loved. She gave an excellent illustration of this with her sculpture Après la tempête (After the Storm), which won her recognition at the 1876 Salon, depicting a grandmother holding the drowned body of her grandson.

After seven years at boarding school, Sarah Bernhardt returned home at the age of 14 to find herself surrounded by women once again: her mother Judith-Julie Bernhardt, her aunts Rosine Berendt and Henriette Faure, her sisters Jeanne and Régina, her teacher Mademoiselle de Brabender, Madame Guérard, “la dame du dessus" (the lady upstairs) (later nicknamed « mon petit’dame » (my little lady) and who would always remain by her side) made up the new gynaeceum in which she grew up.

Sarah Bernhardt lost her father when she was 13, a father whose identity remained uncertain for a long time, she never named him in her autobiography. It was later established that he was Édouard Viel (1819-1857).

Not that there were no men around the actress-to-be: the “family council” that would decide her future included her godfather Régis Lavolie - hated - and her uncle Félix Faure - much loved - as well as Mr Meydieu - an old family friend - the Duke of Morny and her late father’s notary. It was the Duke of Morny, a friend of her mother’s, who committed her to the theatre, “on the strength of a word spoken reluctantly”.

Changing the image of actresses

Sarah Bernhardt did not welcome the idea of entering the Conservatoire, because of the image she had of actresses. As she explained to her mother, actresses “are like Rachel”. And Rachel is a woman “who does a job that kills her”, according to Sister Sainte-Appoline of the Grand-Champs convent, and at whom “a little girl […]stuck her tongue out”. For Sarah Bernhardt, it was out of the question that anyone would stick their tongue out at her when she became “a lady”.

The choice of this term to mark the passage from adolescence to adulthood makes sense: for her, it was not just a matter of becoming a “woman” (an adult female) but a “lady” (a woman from the upper social classes, and therefore respected). By omission and contrast, this use of the word “lady” reveals all that actresses are not, in the eyes of most people.

But Sarah Bernhardt went on to change the image of actresses considerably. With obvious pleasure, in her autobiography as in her theatrical art, she shatters the idea of a rivalry to the death between them, asserting quite the opposite. On the subject of her unexpected success on the evening of her return to the Comédie Française after her London tour, she notes:

She explains this male jealousy by the idea that theatre is an “essentially feminine art”. A “feminine” quality she defines, in line with the collective imagination of the time, as the mastery of seduction:«Some artists were very happy, especially the women, because there is one thing to be noted in our art: men are much more jealous of women than women are of each other.»

«Painting one’s face, concealing one’s true feelings, seeking to please, wanting to attract attention, these are the failings that we criticise in women and for which we show great indulgence»

Sarah Bernhardt transformed these faults attributed to women into a master asset which ensures their supremacy in the theatre, “the only art in which women can sometimes be superior to men”. For her, female painters (such as Madeleine Lemaire, Rosa Bonheur, Louise Abbéma), composers (such as Augusta Holmès and Cécile Chaminade and poets (such as Madame Desbordes-Valmore, Louise Ackermann, Anna de Noailles, Lucie Delarue-Mardrus) of her time, although well-known and recognised, were still far from equalling their male counterparts.

In the theatre, on the other hand, the names of Mademoiselle Duclos, Adrienne Lecouvreur, Mademoiselle Clairon, Mademoiselle de Champmeslé, Mademoiselle Georges, Mademoiselle Mars and Rachel were only opposed by Baron, Talma and Mounet-Sully. Whether we agree with this point of view or not, Sarah Bernhardt was keen to restore the image of actresses, who she considered to be the most accomplished female artists.

Following this logic, she set out to disprove the black legend of fierce competition between Sophie Croizette and herself, describing it as fabricated by outsiders: “War was declared, not between myself and Sophie, but between our respective admirers and detractors”. But she also had the most sympathetic admirers: “all the artists, the students, the dying and the failed” while Sophie Croizette had “all the bankers and the stuffy people”. It has to be said that, unlike her friend, the curvaceous shapes that defined, at the time, the physique of an actress.

A “lack of femininity” turned into a strength

Indeed, her “blonde negro hair”, as the hairdresser who hacked it off on the day of the Conservatoire tragedy contest described it, and above all her “burnt bone” thinness, in the words of an audience member on the night of a performance of Mademoiselle de Belle-Isle - a play by Alexandre Dumas performed by Sarah Bernhardt in 1872 - earned her much criticism and caricature: no sooner had she arrived in America for her triumphant tour than she was sketched as a “skeleton in a curly wig” by a young cartoonist.

In the course of her autobiography, she often refers to the thinness she initially suffered from, which “nourished the inspiration of scathing songwriters and the caricaturists’ albums”. It ended up becoming the physical sign of her exceptional nature, imposing itself as an advantage.

It was her unusual physique that made her stand out, giving her the opportunity to take on special roles: those of male characters. Not that she was the first woman to play men’s roles, especially as in opera, for certain characters entrusted to mezzo-sopranos, the practice of “transvestite” roles was common, as with Cherubino in Mozart’s Les noces de Figaro (The marriage of Figaro) - which Sarah Bernhardt performed in Beaumarchais’s play in 1872. But it was with the role of the troubadour Zanetto in François Coppée’s Le Passant (first performed three years earlier at the Théâtre de l'Odéon) that she achieved her first real success.

Her male roles - Pierrot in 1883 in Jean Richepin's Pierrot Assassin, Hamlet in 1886 and 1899 in Shakespeare’s play, Lorenzaccio in 1896 in Musset’s play, the Duke of Reichstadt in Edmond Rostand’s L’Aiglon in 1900 and Pelléas in 1905 in Maeterlinck’s Pelléas et Mélisande - made a lasting impression on her audiences and gave her the opportunity to explore a new range of emotions, which she relished.

She devotes a chapter to this issue in L’Art du Théâtre, explaining her love for the character of Hamlet:

«No female character has opened up such a wide field for the exploration of human feelings and pain as Hamlet. […] I can say that I have had the rare, and I think unique, opportunity to play three Hamlets: Shakespeare’s black Hamlet, Rostand’s white Hamlet, L’Aiglon, and Alfred de Musset’s Florentine Hamlet, Lorenzaccio».

However, she immediately sets out the imperative conditions for a woman to take on a male role:

«A woman can only play a man’s role when he is a brain in a feeble body. A woman couldn’t play Napoleon, Don Juan or Romeo. Mephisto... yes, because he is in fact a fallen angel, the evil spirit who accompanies Faust».

The role of Mephisto is a turning point in her thinking, because he is an “angel”, a sexless being, a “spirit”, an asexual being. But precisely, she considers that male roles such as those of the “three Hamlets” are in fact sexless roles: “Any artist [who wants to play these roles] must be stripped of their virility”, because Hamlet is “a ghost amalgamated from the atoms of life and the decay that leads to death”. And to conclude:

«these roles will always benefit from being played by intellectual women, who are the only ones who can preserve their sexless character and their aura of mystery».

Of course, Sarah Bernhardt seems to forget that not all actresses have her unique physique, neither feminine nor masculine, a sort of third, sexless gender (and not androgynous, which combines feminine and masculine traits), but that is one way of concluding in her favour: Sarah Bernhardt imposes her gender.

This reflection on male roles stems from a comparison between Cornelian heroines (described as “hysterical reasoners”) and Racine’s heroines, ending up in favour of the latter. According to Sarah Bernhardt, only Racine’s heroines (of whom Phaedra is for her the emblem, and the only female role to equal that of Hamlet) are truly “feminine”, because they try to conceal what they really feel until the very end, only bursting out of the social corset in desperation.

In her own way, then, by discussing the verisimilitude and interest of women’s roles, Sarah Bernhardt rejects the clichés associated with a pseudo-nature of women (no, women are neither furies nor hysterical) and considers a historical and social fact (the need for them to conceal their innermost selves) which she sees as decisive in the construction of female characters, both real and fictional.

For Sarah Bernhardt, this need to conceal goes hand in hand with women’s ability to assimilate, as she explains in L’Art du Théâtre: “You can make an adorable duchess out of a Parisian errand girl in just a few years. You can never make a duke out of a scoundrel or a bourgeois.”

In doing so, she also notes how difficult it is to break free from the collective imagination that determines a general image of “the” woman, specific images of “types” of women and timeless images of feminine heroism.

Creating one’s own heroism

After having missed out on first prize in the Conservatoire comedy contest, Bernhardt seems to have been prompted to reflect on the difficulty, as an actress, of (re)creating female characters. While the first prize in comedy went to her friend Marie Lloyd, Sarah Bernhardt only received second prize. But for her, the die was cast:

“It w as a beauty prize that was awarded to Marie Lloyd! [...] Despite [...] the impersonal nature of her acting, she won the vote: because she was the personification of Célimène [...]. For everyone, she achieved the ideal Molière dreamed of.”

With this anecdote, Sarah Bernhardt points out how many fictional characters have a pre-established image and how difficult, even futile in some cases, it is to try to replace them with another, in keeping with one’s own physique and character. Admittedly, like any reader, she too first sees a “materialised vision” of the character, but she then works to try to perceive him as the author imagined him, even if it means going against the sometimes longstanding image that the public has of him.

She concedes, however, that it seems impossible to destroy the “legendary aspect” of a character who has become mythical, even if the work of historians has re-established the truth. She lists both male and female characters as examples, but focuses on Joan of Arc (whom she played in Jules Barbier’s play in 1890 and in Émile Moreau’s in 1909):

“We don't want Joan of Arc to be a crude, galliard peasant woman who violently rebuffs a roughneck mercenary who wants to banter, who rides like a man on a large Percheron horse, who willingly laughs at soldiers’ ribaldry, and who is subjected to the indecent promiscuity of her still barbaric era [...]. In legend, she remains a frail being driven by a divine soul. Her maiden arm holding the heavy standard is supported by an invisible angel”.

By analysing the public image of Joan of Arc, Sarah Bernhardt approaches the question of feminine heroism and notes how it is inseparable from an ethereal physical appearance, elegant gestures and a physical purity that bears little resemblance to reality. This curbed her taste for realism, and she gave up the fight.

Taking on the role of a female character becomes even more complicated when you add in the real faces that have been associated with her over the centuries. And if we adopt Sarah Bernhardt’s assertion that, in theatre, the names of actresses are more readily remembered than those of actors, then the challenge of taking on a role in which an actress has distinguished herself is all the greater.

The role of Phaedra, for example, was a challenge for her, because Rachel - twenty years her elder - had imposed her own features on this heroine in 1843, and the memory of her was still vivid when Bernhardt was given the role thirty-one years later, knowing full well that there would be no shortage of comparisons.

On this occasion, however, Sarah Bernhardt triumphed and only mentioned one unfavourable article in her autobiography, by Paul de Saint-Victor, who she said was “related to one of Rachel’s sisters”; a way of highlighting the critic’s partiality.

Similarly, in 1880, when she played the role of Adrienne Lecouvreur =(confronting her first image as an actress!) in the play (bearing her name) dedicated to her by Ernest Legouvé and Eugène Scribe in London, she was again compared to Rachel - who had created the role in 1849 - by Figaro critic Auguste Vitu, “regretting [that she had] not followed Rachel’s traditions” but also admiring in her, in Act V, “a dramatic power[...], a truth of accents that cannot be surpassed” and “a science of composition that she had never revealed before”.

Sarah Bernhardt always made the same objection to these comparisons: she had never seen Rachel play these roles, which, despite Rachel’s fame, gave her the creative freedom she needed.

However, the reputation of a more distant predecessor can be a source of inspiration. For the role of Phaedra, for example, Sarah Bernhardt confided that she relied on the reputation of Mlle de Champmeslé (1642-1698)), remembering that “according to historians, she was a creature of beauty and grace, not a madwoman”, which supported her interpretation of Phaedra as “the most touching, the purest, the most pained victim of love”.

These reflections on the creation of female characters all seem to have fed into Sarah Bernhardt’s thinking about the creation of her own “personality”. She seems to have combined her study of the roles she was given with introspection and self-development.

Very early on in her autobiography, she speaks of a desire for self-affirmation and recognition by others that she felt as a child, and whose first realisation dates back to her time at the Grand-Champs convent: “At last, I had become a personality, and that satisfied my childish pride”, she wrote.

Creating a personality

“Personality” is an important term for Bernhardt, and she uses it several times in the course of her narrative: in its two main meanings, it defines both what she already is - a strong individual who stands out from the others - and what she wants to be - an important person.

She often uses it with this double meaning, as when she waits, anxious yet sure of herself, to be given a “part” (and not a “role”, as a religious play requires) in the play TTobie recouvrant la vue (Tobias Regains His Sight) that the convent’s pupils are to perform on the occasion of the visit of the Archbishop of Paris, Monsignor Sibour.

But this double meaning of the word is even more clearly expressed after her first public and social success, namely her success in the entrance examination for the Conservatoire: “I felt the need to create a personality for myself. It was the first awakening of my will. I wanted to be someone”.

In fact, the title of her autobiography, Ma Double vie (My Double Life), does not refer solely to this life divided between the stage and the city, the mechanism of which she describes in detail during a performance of Mademoiselle de Belle-Isle.

It also echoes the battle that has often pitted her two selves against each other, as when she waits feverishly for the result of the Conservatoire comedy contest:

“The craziest, most illogical battle imaginable was being waged in my frail young mind. I felt every calling to the convent, in my distress at missing out on the prize; and every calling to the theatre, in the hope of winning the prize”.

But these two forms of “self” were reconciled in their ambition, which was nothing less than to become “the Mother President of the Grand-Champs convent” in one case, and “the first, the most famous, the most envied” of actresses in the other.

Although her inner dilemma was quickly resolved - she would become an actress - the multiple identities she embraced were not confined to the stage: Sarah Bernhardt also played many roles in the city. She thus built her fame on this kaleidoscope of identities, as much as on her talent: Sarah Bernhardt was a nurse and a patriot - transforming the Odeon into an ambulance during the Prussian War, boosting the morale of the soldiers in 1914 -, Sarah Bernhardt was an adventurer - travelling in a balloon, descending into the crevasse of the “Plogoff Inferno”, touring the wilds of America -, Sarah Bernhardt was a sculptor, Sarah Bernhardt was a painter, Sarah Bernhardt was a ghoul sleeping in a coffin, and much more.

The actress is the talk of the town, even if she denies knowledge of this, claiming only to live freely and according to her whim. Her American impresario, Edward Jarrett, was determined to capitalise on Bernhardt’s aura and name, which he sold both in the world of show business and in advertising.

On the other hand, on several occasions the actress felt her image slipping away from her and was sometimes tricked, as in the episode of the Boston whale where a certain Henry Smith, a fishing boat owner, almost forcibly dragged her onto the back of a dying cetacean, from which he had her rip off a baleen plate to make a poster and advertisements, turning the dying (or even dead!) animal into a lucrative tourist attraction.

Sarah Bernhardt was so accustomed to playing with interpretations of her different selves that even in her autobiography, she only revealed selected parts of herself. On the one hand, she carefully attests to the veracity of her account (sometimes from an apologetic point of view), taking care to cite as evidence the “quantity of documents” kept “preciously” by Madame Guérard or the “small notebooks” in which her secretary had “orders to cut and paste [...] everything that was written about her, whether good or bad”.

On the other hand, she reserves the right of omission (lying by omission, some would say), revealing little of her private life::

“But I want to set aside in these Memoirs anything that relates to the direct intimacy of my life. There is a family “I” that lives another life, and whose sensations, joys and sorrows are born and die for a very small group of hearts.”

It is true that Sarah Bernhardt tells “the story of her personality” , but as she invented and sculpted it and as she wished it to be seen: sphinx and chimera, like the inkwell she had fashioned in her likeness and in which she seems to have dipped her pen and diluted her mysteries.

Identity card of the article

| Original title: | Sarah Bernhard, l'actrice qui sut imposer son genre |

| Author: | Ambre-Aurélie Cordet |

| Publisher: | The Conversation France |

| Collection: | The Conversation France |

| License: | This article is republished from The Conversation France under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. An English version was created by Hancock & Hutton for Université Gustave Eiffel and was published by Reflexscience under the same license. |

| Date: | June 4, 2024 |

| Langages: | French and english |

| Keywords: | literature, gender, masculine-feminine, theatre, femininity, feminism, history of the arts |

![[Translate to English:] Licence creative commons BY-SA 4.0 [Translate to English:] Licence creative commons BY-SA 4.0](https://reflexscience.univ-gustave-eiffel.fr/fileadmin/ReflexScience/Accueil/Logos/CCbySA.png)