How to republish

Read the original article and consult terms of republication.

Unemployment figures at a record low but mask widening inequalities between regions

In the fourth quarter of 2022, the employment market was strong despite the gloomy macroeconomic context. With 2.2 million people in unemployment, as defined by the International Labour Office (ILO), France's unemployment rate stands at 7.2% of the working population, while the labour force participation rate is at an all-time high.

This positive situation in the employment market is reflected in the difficulties experienced by companies in hiring staff, particularly in construction, transport and certain industrial professions. In addition, companies’ profit margins are on the rise and, in 2022, CAC 40 companies were particularly generous, distributing a record €56.5 billion in dividends to their shareholders.

This situation owes much to the fact that the economy has been heavily subsidised since the Covid-19 pandemic, with measures such as emergency support (the “whatever the cost” approach), the “France relance” and “France 2030” plans, new exemptions from social security contributions and the cancellation of the corporate value-added contribution for two years. Measures to limit the effects of rising energy prices have recently been added to the list of public support for businesses.

This massive injection of public money into the economy with no counterpart in terms of employment or investment is worrying. It raises questions about the resilience of the French economy and its ability to bounce back. There is also the question of the sustainability of this situation, which calls for serious reflection on the current and future economic challenges.

Is everything as good as it seems?

In reality, the French economic situation is more mixed. Several indicators, such as the rate of non-take-up of social benefits, reveal areas for concern. Rising energy and food prices are also weighing heavily on the most vulnerable households.

There are also worrying signs in the industrial sector, with the PMI index (which measures the level of activity of purchasing managers) for the manufacturing industry in the eurozone at its lowest in 29 months. This affects the automotive production, coking and refining, the extractive industries and the water and sanitation sector.

France's external competitiveness is also at risk of falling further behind as a result of the escalating war in Ukraine, which could lead to higher production costs for businesses. Supply tensions and rising interest rates are other factors weighing on the French economy. Lastly, the fall in the number of building permits recorded by the French Building Federation (Fédération Française du Bâtiment) presages a possible decline in activity among construction companies in the medium term.

This combination of an unemployment rate at its lowest since 2008 and major macroeconomic difficulties is sufficiently exceptional to worry forecasters. For example, the Banque de France points out that although French GDP growth is expected to reach 0.6% in 2023, it will still be lower than the average for Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, which stands at 0.7%.

Lastly, there is still no reduction in inequalities. Although the situation of older people is improving, with increases in the minimum old-age pension and the disabled adult allowance, the planned pension reform could penalise women while the situation of young people is deteriorating (insecure jobs, low wages, above-average unemployment).

These social inequalities are compounded by regional inequalities.

Some regions left out

Already weakened by the downward trend in industry, the economic shutdown during the Covid-19 crisis and price pressures resulting firstly from recovery and secondly from the war in Ukraine, many regions are now exposed to considerable economic risk.

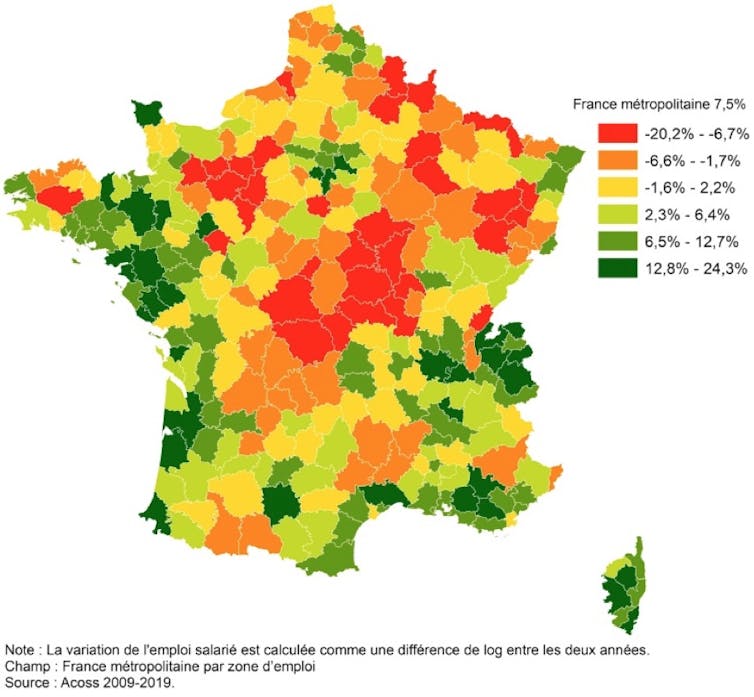

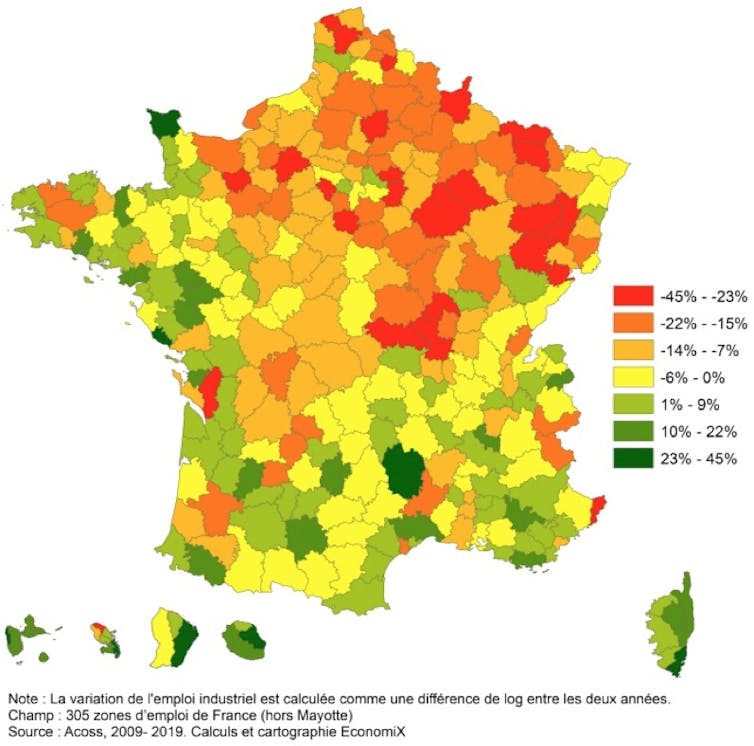

The trend in private salaried employment in all sectors, including industry (see maps below), within the different employment zones, reflects the unchanging - and even worsening - disparities between the “arid diagonal” and the coastal areas. An employment zone is defined as a group of municipalities in which most of the working population lives and works, and where establishments can find most of their workforce. The delimitation by the French National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies (Insee) in 2020 defined 305 employment zones. These zones are considered the most appropriate spatial mesh for local economic studies.

Change in private-sector salaried employment in industry between 2009 and 2019

Change in private-sector salaried employment in industry between 2009 and 2019

The study carried out on these employment zones showed that regions with a strong industrial past (Grand-Est, Hauts-de-France, Seine-Aval and Centre), which had already been severely hit by deindustrialisation before the health crisis, could be even more strongly affected. However, this is also the case in areas that have been relatively spared until now, such as the Loire Valley and Brittany, where the number of business bankruptcies rose sharply last year.

The traditional shock absorbers, such as public employment and the local economy, no longer seem to be playing their role, while the impact of the economic drivers of resilience (industrial specialisation, agglomeration effects, knowledge-intensive services) is limited to metropolitan areas. This dynamic is also true for industry. Between 2016 and 2019, 60% of industrial jobs were created in conurbations and their surrounding employment zones.

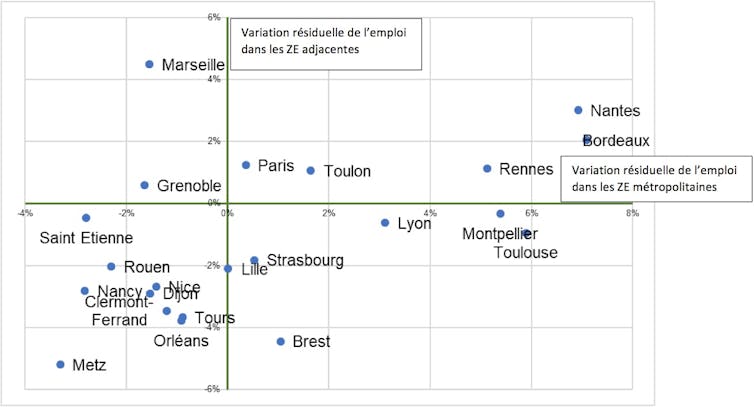

For all that, not all metropolitan areas are doing well. While Rennes, Nantes and Bordeaux are enjoying employment growth, many are also experiencing difficulties (Grenoble and Saint-Étienne, for example). The situation of metropolitan centres also varies in different ways in parallel with that of neighbouring employment zones. For example, the figure below shows that some metropolitan areas have a similar employment dynamic (residual variation in employment in metropolitan employment zones) to that of their periphery (residual variation in employment in adjacent employment zones). This synchronised change can be positive, such as in the three cities in western France, or negative, such as in Metz, Clermont-Ferrand and Nancy. Changes can also be asynchronous, such as in Marseille where jobs are being created in the city centre but destroyed on the outskirts, while the opposite is happening in Strasbourg and Brest. These divergent situations call into question policies centred on metropolises alone, in favour of more locally based approaches.

A gloomier future is plausible

While the government's announcements and current reforms (unemployment, pensions) are based on the assumption of an economic recovery and renewed growth, another, less radiant future looms on the horizon in the medium to long term. Early warning signs suggest that local shocks of unequal magnitude could be superimposed and exacerbate disparities between regions.

Moreover, against a backdrop of high inflation, most local authorities will see no change in their overall operating grants (DGF), which raises questions about the future of local public services that are essential to the ecological transition, social cohesion and regional equality, with urban public transport at the top of the list.![]()

Identity card of the article

| Original title: | Chômage : un chiffre au plus bas mais qui masque le creusement des inégalités entre les territoires |

| Authors: | By Nadine Levratto and Philippe Poinsot |

| Publisher: | The Conversation France |

| Collection: | The Conversation France |

| License: | The original version of the article was published in French by The Conversation France under Creative Commons license. An English version was created by Hancock & Hutton for Université Gustave Eiffel and was published by Reflexscience under the same license. |

| Date: | July 20, 2023 |

| Languages: | English (a French version is available) |

| Keywords: | Unemployment, job, inequalities, industry, territories, deindustrialization |

![[Translate to English:] Licence creative commons BY-SA 4.0 [Translate to English:] Licence creative commons BY-SA 4.0](https://reflexscience.univ-gustave-eiffel.fr/fileadmin/ReflexScience/Accueil/Logos/CCbySA.png)