How to republish

Read theoriginal article in french and consult terms of republication.

Bank branch closures: a trend that began well before the pandemic

The Covid-19 pandemic has de facto led to many bank branch closures in France for various periods of time, restarting the debate in the press around whether this is a fundamental trend that can be traced back to the growing digitalisation of the banking model.

In December, it was announced that the networks of Société Générale and Crédit du Nord would be merged, meaning the closure of 600 branches across France by 2025. This has confirmed the beliefs of people in this movement.

However, the current pandemic can actually only be playing a minimal role in feeding this trend, which has greatly intensified in recent years, specifically since 2013.

A movement that is nothing new

Using the OGRB database, which collects and geolocalises the physical position of bank branches for all banks in France annually, we were able to quantify this phenomenon across the 1999-2018 period. It was quite significant during this time, with 8,363 branches closing across 11 banks, representing the equivalent of 19.9% of branches that existed at the start of this period (end of 1998).

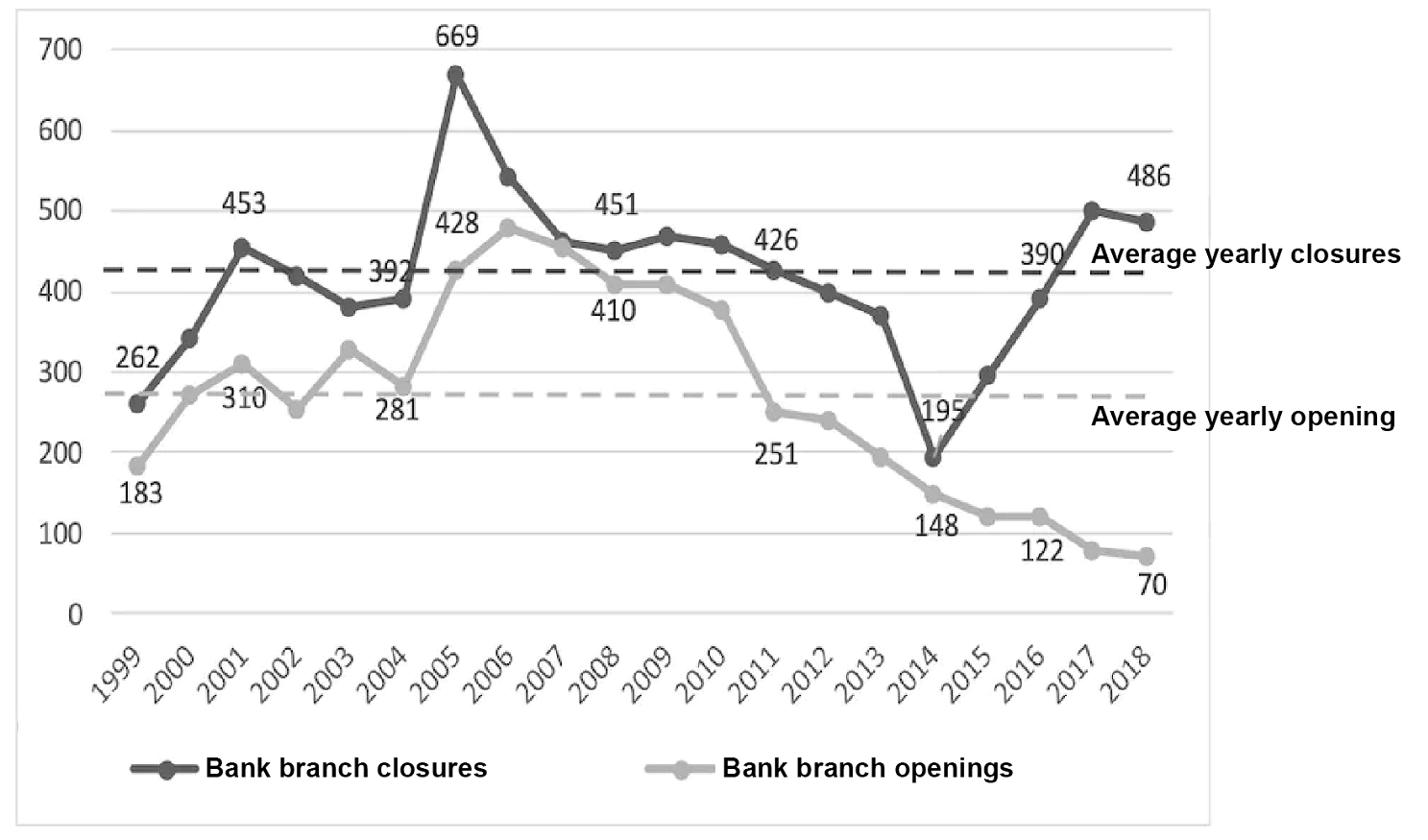

Graph 1 shows the annual branch openings and closures during this time. If we compare the curve of closures to the yearly average for the 1999-2018 period (418 branches), it shows that this phenomenon is not a recent one.

Furthermore, when comparing with openings, we see that there were more branch closures than openings throughout this period, which gives a net loss, slowly eroding the number of bank branches in France.

This net loss increased in the last phase studied, with a clearly visible scissors effect: the annual level of closures increased, while the decrease in openings that began in 2007 continued, thereby intensifying the phenomenon, in line with the first reports of branch closures in the press.

Organisational mimicry?

The banking sector remains characterised simultaneously by high structural uncertainty amplified by transformations in the competitive landscape and distribution models under the impact of new technologies – and high levels of organisational legitimacy, given that the sector is both highly regulated and deemed trustworthy by the public.

The academic literature, in both behavioural finance (studying herd behaviour) and strategy (neoinstitutional theory), highlights that a sector presenting the aforementioned characteristics lends itself well to organisational mimicry, leading to more homogenous behaviour and practices among organisations.

In financial economics, the emphasis is placed on profitability as an indicator to guide decision-making, with a rational calculating approach. More specifically, the incentive to imitate comes from uncertainty around the bank’s ability to predict whether a branch will continue to generate sufficient profit. So, the bank will opt to observe and imitate what the competition is doing with their closure decisions. The profitability indicator is now even more essential in the context of low rates, which means low lending margins.

Within the framework of neoinstitutional theory, banks imitating each other in deciding to close branches is mainly done with the aim of strengthening their legitimacy, by copying competitors that belong to groups considered to be benchmarks..

Sequenced communications

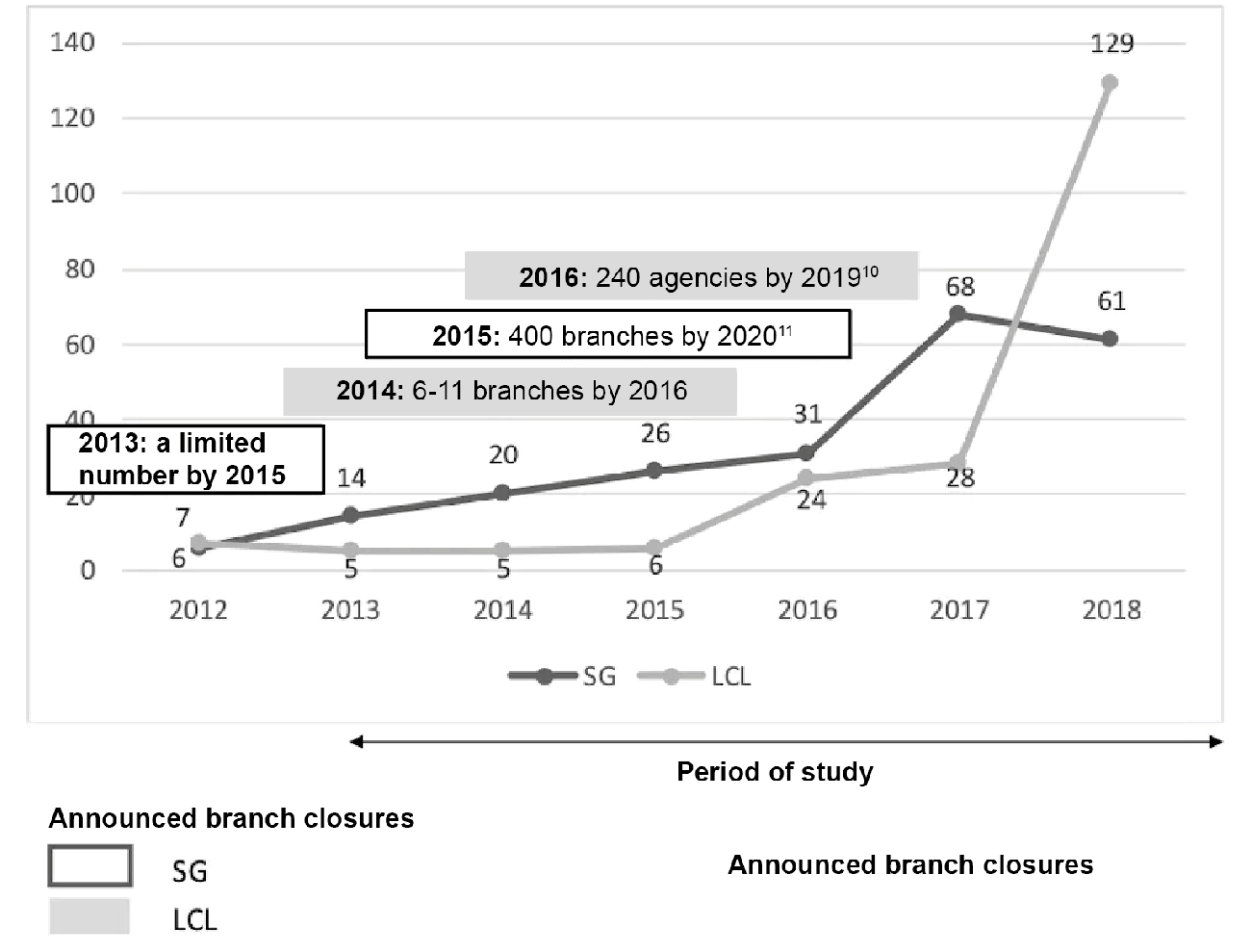

As a case study, we analysed branch closures by two national banks, LCL and Société Générale (SG), across the 1998-2013 period. Data from the OGRB database showed that these banks closed 10% of their branches on average from their baseline in 2012 (respectively, 10.4% for LCL and 9.6% for SG) and that the yearly average for the number of closures was the same (35 branches per year).

We compiled the choices and causes behind the closures by undertaking documentary research (count and content analysis of 91 articles from the national and regional daily economic press published between 2012 and 2018). The main common theme that emerged is that LCL and SG announced major branch closures during this period as a key part of their strategic plans.

Graph 2 shows that LCL follows SG in implementing its branch closure policy, which supports the analysis of sequenced corporate communications from the two banks. In 2014, LCL announced closures one year after SG did so in 2013, then again in 2016, one year after SG.

In terms of causes, in 2014, LCL cited shifts in customer expectations towards the remote channels provided by online banking, while the 2016 branch closure announcement was connected to the bank’s economic performance, which, in the words of its main shareholder, “did not deliver the desired results”.

As for SG, it mentioned similar causes in justifying the closures announced in the press in 2014 and 2016, i.e., the decrease in the bank’s revenue and resulting cost-cutting, as well as the widespread use of the internet and smartphones.

In this way, a cluster of elements came together for LCL’s behaviour to imitate SG’s.

Social and political consequences

While these closures are justified by the ex ante lack of profitability, there is a broader debate around the geographical phenomena that they cause. Branch closures are not free of social and political consequences, particularly in economically fragile areas.

The justification of a drop in visits to branches due to online transformations remains debatable. Economically fragile retail banking clients often need to “come in to the bank” to manage their budget and obtain banking services that are not available online (chequebook, cash etc.). Branch closures could therefore lead to this clientele having to leave the bank.

Furthermore, there is a paradox between the importance of professional and small business clientele for French banks, which is always highlighted in their annual reports, and the complete lack of mentions of this clientele when justifying branch closures in the press.

Only the transition to online banking for private individuals and their fewer trips to the branch are evoked as causes for closures. However, professionals and small businesses also need face-to-face interactions with their banking advisor, if only because the process of obtaining a loan is not yet available online.

Depending on the network, professional and small business clientele may be seen in branches or centres specifically for them, or in branches where they co-exist with private clientele. A supplementary avenue for research would involve examining mimicry behaviour between networks opting for the same organisational structure (representing therefore a reference group), continuing the investigation of choices to close bank branches.

Identity card of the article

| Original title: | Fermetures des agences bancaires : une tendance amorcée bien avant la crise sanitaire |

| Authors : | Sophie Serve et Evelyne Rousselet |

| Publisher : | The Conversation France |

| Collection : | The Conversation France |

| Licence : | The original version of the article was published in French by The Conversation France under Creative Commons license. See the original article. An English version was created by Hancock & Hutton for Université Gustave Eiffel and was published by Reflexscience under the same license. |

| Date of publishing: | April 20, 2023 |

| Languages: | english and french |

| Keywords : | finance, strategy, bank, economic theory, customer relations, behavioural economics |

![[Translate to English:] Consultez le site web The Conversation France](https://reflexscience.univ-gustave-eiffel.fr/fileadmin/_processed_/7/c/csm_TC_Stacked-ENG-FR_d13cf8099d.png)

![[Translate to English:] Licence creative commons BY-SA 4.0 [Translate to English:] Licence creative commons BY-SA 4.0](https://reflexscience.univ-gustave-eiffel.fr/fileadmin/ReflexScience/Accueil/Logos/CCbySA.png)