How to republish

Read the original article and consult terms of republication.

Commuting between cities: an overlooked aspect of mobility

Credit : Benoit Conti et Sylvestre Duroudier / Atlas des déplacements domicile-travail

interurbains.

Working in a city other than one’s place of residence is becoming increasingly common in France. A recently published atlas examines the geography of these flows, which are predominantly car-based, and how some of them could be replaced by public transport.

In France, cars are used for 75% of commutes. These journeys are also responsible for a quarter of greenhouse gas emissions from private cars.

While most people work in the city where they live, 3 million people (10% of the working population) are employed in another city. This is 50% more than twenty years ago. There are many reasons for this: rising property prices, changes in the job market, changes in lifestyles and work patterns, etc.

According to INSEE, these journeys average 35 km (one way), which is three times the average commute. In over 90% of cases, they are made by car and now account for a third of greenhouse gas emissions from all commuting journeys. However, they are not really taken into account in discussions on reducing greenhouse gas emissions from everyday travel.

How can we define a city?

The term ‘city’ here refers to the catchment areas defined by INSEE in 2020. A catchment area consists of a core area (a set of municipalities defined according to criteria of density, employment and population) and its peri-urban municipalities, which are those that send at least 15% of their workforce to the core area. The most populated municipality of the core area is defined as the centre of the catchment area.

Visualising these interurban flows...

As part of a partnership with transport operator Transdev, we have produced an Atlas des déplacements domicile-travail interurbains en France continentale (Atlas of interurban commuting in mainland France). Based on data from the 2018 census, it allows these flows to be visualised and characterised at national and regional levels, and provides food for thought regarding the requisites for shifting them to public transport.

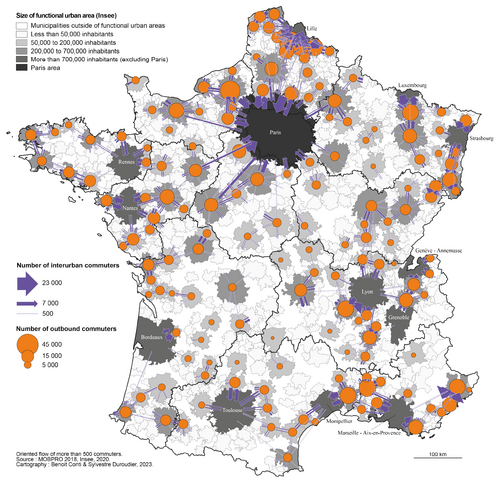

The Atlas focuses on cities with between 50,000 and 700,000 inhabitants, which are the origin or destination of 80% of inter-city commutes in France. The map below, which is taken from the Atlas, shows the most important connections, i.e. those with at least 500 commuters (in one direction).

Commutes to and from cities with a population of between 50,000 and 700,000

Commutes to and from the Paris catchment area involve around 100,000 people, representing a minority of the inter-city commutes studied in the Atlas. These journeys are also unusual in terms of the mode of transport used.

The performance of rail links, the long distances travelled and traffic and parking difficulties in the Paris conurbation all encourage the use of public transport much more than elsewhere. Commutes between Paris and Reims are typical of this situation: half of the workers concerned travel to work by public transport, compared with 10% for all inter-city journeys.

Elsewhere, inter-city commuting patterns vary, with a few typical examples emerging:

- Hubs around large cities (such as Rennes, which has a lot of traffic with Vitré, Fougères and Saint-Malo) or smaller cities (e.g. around Bourges);

- Multipolar systems, for example around Nantes, which has significant exchanges with Angers, Cholet and La Roche-sur-Yon, and where flows are also significant between these cities (differentiating it from a hub system);

- Corridors (such as Nancy-Metz-Thionville or Perpignan-Avignon);

- And even intense exchanges between two cities of similar size (e.g. Pau and Tarbes, or Belfort and Mulhouse).

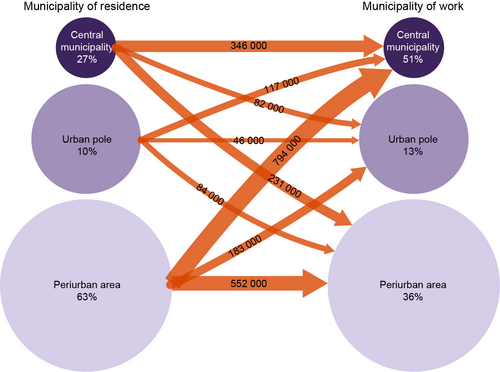

On a smaller scale, as shown in the illustration below, the most significant flows connect a peri-urban municipality to a centre (in the sense of the main municipality of a catchment area), or two peri-urban municipalities.

Which municipalities are connected by inter-city commutes?

Inconsistent availability of public transport

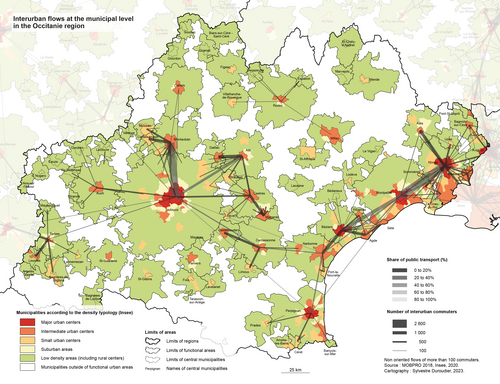

Depending on the origini and destination, the volume of traffic and the share of public transport vary greatly, as shown on the map of the Occitanie region. Inter-city commutes are fairly scattered and dominated by cars between the suburban municipalities of Montpellier and the central municipality of Nîmes. In Béziers, a certain dispersion of flows is also observed. In other cases, inter-city workers are more concentrated on connections between two centres, for example between the centres of the cities of Castres and Mazamet, or those of the cities of Carcassonne and Limoux.

Municipal configurations of inter-city commutes in the Occitanie region

Could these journeys be made without a car?

Some public transport lines are already relatively well used by people who work outside their city of residence: this is more often the case when the job is located in a city with more than 700,000 inhabitants, when the person lives in a centre and also works in a centre, when the residential and work municipalities are located less than 10 km from a train station, or when the journey time by road exceeds 45 minutes. However, there is still considerable room for improvement.

Reducing private car use for some commutes between cities is complex, but not impossible. Depending on the situation, it seems more appropriate to consider increasing the use of existing public transport lines or creating new lines or even carpooling services.

Improving the current public transport service (trains or buses) also requires consideration of how to adapt timetables (morning and evening rush hours), frequencies (particularly in the evening, to take family constraints into account) and fares (e.g. to target long-distance commuters) in order to better meet the needs of individuals.

This policy of increasing supply makes particular sense for journeys characterised by high volumes of commuters and for which public transport is already widely used, for example between Rouen and Yvetot. Policies encouraging people to switch to public transport should also be considered, particularly in suburban municipalities: cycle paths, secure bicycle storage facilities, park-and-ride facilities with free or low-cost parking for public transport users.

The creation of new services should focus on routes with high passenger volumes and, depending on the case, consider new rail infrastructure or the introduction of express bus services, such as the one that exists between La Rochelle and Niort.

On routes involving slightly fewer commuters and intermediate distances (typically 10 to 30 km), carpooling services are one of the appropriate options.

The issue is not only technical, but also political, as interurban journeys transcend the boundaries of AOMs (the authorities responsible for organising mobility in France). Finally, the challenge of better managing inter-city commutes is not only environmental. It is also social, given the difficulties certain groups face in accessing employment and housing, and the high mobility costs for these commuters due to the distances travelled.![]()

Identity card of the article

Original title: | Les déplacements domicile-travail entre villes, un impensé de la mobilité |

Author: | , , |

Publisher: | The Conversation France |

Collection: | The Conversation France |

Licence: | This article is republished from The Conversation France under Creative Commons licence. Read the original article. An English version was created for Université Gustave Eiffel and was published by Reflexscience under the same license. |

Date: | July 29, 2025 |

Languages: | French and English |

Key words: | Transport, regional planning, cities, mobility, ecological transition |

![[Translate to English:] Licence creative commons BY-SA 4.0 [Translate to English:] Licence creative commons BY-SA 4.0](https://reflexscience.univ-gustave-eiffel.fr/fileadmin/ReflexScience/Accueil/Logos/CCbySA.png)