How to republish

Read the original article and consult terms of republication.

The forgotten victims of the agricultural crisis: no right of residence for foreign seasonal workers?

By Gaëlla Loiseau from Inrae, Anne Lascaux from Université Gustave Eiffel, Béatrice Mésini from CNRS and Aix Marseille Université

Credit : Lucie Hautbout / Gabrielle Bichat

In February 2024, a few months after the adoption of the much-publicised Immigration act a a ministerial directive was issued which formalised an exceptional admission process granting residency to workers without a residence permit who were employed in professions and geographic areas characterised by recruitment difficulties. A clear indicator of the French government’s desire to “promote work as a factor of integration”, it strikes a balance between commitments made to farmers, who are particularly concerned by the recruitment of foreign seasonal workers, and pledges made to right-wing far-right parties.

It is worth remembering that the intrinsic vulnerability of the “seasonal” worker status can lead to exploitation and many kinds of abuse.

Hired on a temporary basis, these foreign workers are re-employed each year by the user companies, often on a revocable basis.

Initiated after the war to make up for the shortage of farm workers following the rural exodus, the employment of foreign seasonal workers in agriculture in France was first organised on the basis of bilateral labour agreements: with Italy in 1951, Spain in 1961, Morocco, Tunisia and Portugal in 1963, Yugoslavia in 1965, etc…

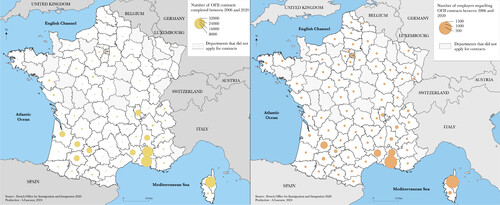

These “introduction contracts”, previously issued by the French Office for International Migration (OMI), are now issued by the French Office for Immigration and Integration (OFII). They grant the holder the right to work in France for a period not exceeding 6 consecutive months, provided that they cannot be recruited locally. Since the 1970s, these contracts have been widely used within the French agricultural industry and the system has rarely been called into question over the course of the 20th century.

One thing that has changed since the 1970s is temporary workers' knowledge of employment law and the increasing number of legal disputes. In the early 2000s, the Collective for the Defence of Foreign Agricultural Workers disclosed a number of illegal practices carried out by companies: longer working hours, no weekly rest period, underpayment for hours worked, lack of information on the risks and protection required when handling chemical ingredients and pesticides, etc.

On 12 July 2005, a strike was called by 240 Moroccan and Tunisian workers on seasonal contracts to denounce their working and accommodation conditions and demand compensation for 200 to 300 hours of unpaid overtime. On 20 July 2005, 150 other farm workers also went on strike over pay and housing.

In 2008, the French Equal Opportunities and Anti-Discrimination Commission issued an opinion on the discriminatory nature of the restrictions imposed on these North African farm workers, employed for several years by the same employers on 8-month contracts. It acknowledged that this practice prevented the application of provisions relating to employment and social protection “because of the status in which they were confined with the assistance of the administration”:

“There is discrimination and a breach of equal treatment with regard to the right of residence, unemployment benefit and rights concerning the workers’ living and working conditions“.

Crédit : OFII, 2020

Competition and vulnerability

After the strikes in 2005, employers looked to diversify their recruitment channels. Since a 1996 directive, a country belonging to the European Union can authorise companies to post workers in another member country for a defined period.

In addition to seasonal contracts, agricultural businesses began to use Latin American and African workers from Spain, sent over by temporary recruitment agencies in the country. According to figures published by the French Directorate of Research,Economic Sudies and Statistics (Dares), there were 8,444 posted workers in agriculture and 14,435 in services related to the sector (which includes a range of farm-related tasks such as sorting, packing and quality control) in France at the end of 2019.

Many of these agricultural businesses renew workers’ contracts and assign them to the same positions throughout the year, which is prohibited under French law, despite the fact that a European directive introduced in 2018 requires Member States to ensure that companies seconding these workers guarantee them equal rights with nationals if the assignment lasts longer than 12 months (with an exceptional extension of 6 months possible).

“Exposure to danger” with complete impunity?

As part of our research, we met Colombian worker Rodrigo, who arrived through a service provider in 2022. He told us about the daily difficulties of his work on a farm in Occitania in 2021, describing the performance requirements - under threat of being sent back to Spain – and health risks he experienced as a posted worker:

“We worked while the farmers were spraying pesticides. The farms’ permanent employees and the managers wore protective gear, and we were there working while they treated crops with the chemicals”.

If a worker dies or is injured or hurt and there is a conviction, most foreign service providers go into receivership and French employers declare bankruptcy to avoid paying the sums ordered by the courts. In practice, it is virtually impossible to obtain compensation for the harm and damages suffered.

Back in 2019, court rulings condemned certain Spanish service providers who seconded workers from their country (Safor Temporis, Laboral Terra, Terra Fecundis) for acts of bargaining, illegal employment, failure to establish the company in France (since almost all of the activity is carried out there), contribution fraud and undeclared and/or unfit accommodation, a ruling that once again revealed the illegality of practices in the market gardening, arboricultural and winegrowing sectors. In the light of this, the French ministers of the interior and labour decided to “strongly reinforce sanctions against employers who hire undocumented workers”.

What changes will the 2024 Immigration Act bring?

In an attempt to strike a balance between freedom, control and the repression of offences, the 2024 Immigration Act tightens entry and residence requirements for foreign nationals, while at the same time cracking down on undeclared work among user companies.

The law adopted in January 2024 sets out three interconnected objectives: strengthen “the articulation between labour needs and access to residence through work”; “strengthen public action to prevent and punish the exploitation of workers without work permits” and “ensure the autonomy of undocumented foreign nationals vis-à-vis their employers by opening up a pathway to residence on their own initiative”.

The following offences constitute illegal employment: concealed work, bargaining, unlawful lending of labour, employment of foreign nationals not authorised to work, unauthorised cumulation of employment, fraud or false declarations.

When the acts are committed “in an organised gang”, “in circumstances that directly expose foreign nationals to an immediate risk of death or injury likely to result in permanent mutilation or infirmity” or “have the effect of subjecting foreign nationals to living, transport, work or inhumane accommodation conditions...”, they are punishable by 10 years' imprisonment and a fine of €750,000 (Article L823-3 of the CESEDA).

However, it is up to the inspectors to agree on the amount of the fine and the judges to decide on the extent of the penalties, depending on the offender's financial capacity, the intentional dimension of the offence and the seriousness of the facts.

Another aim of the new law is to “put an end to the dependency of foreign employees on their employers” by allowing them to obtain “exceptional admission to residency through work” in a sector under pressure. However, article L435-4, of the new law, like the directive of February 2024, explicitly excludes the consideration of work carried out under the cover of “seasonal worker”, “student” or “asylum seeker” residence permits, signalling discrimination against agricultural workers of non-EU origin.

A new crisis with protests in the agricultural sector

In a final piece of legislation, following farmers' protests, the decree of 1st March 2024 opens up residence to “employees” in agriculture, livestock farming, market gardening, horticulture, viticulture and arboriculture, allowing them to apply for an “agricultural” residence permit.

In response, the French Federation of Farmers’ Unions (FNSEA) will henceforth take responsibility for recruiting foreign workers from outside the European Union through its new seasonal farm staff recruitment service (Mes Saisonniers Agricoles), organised in partnership with the ministries and employment partners of Tunisia and Morocco, offering farmers secure, high-quality recruitment in the shortest possible time. It is a curious turn of events, given that in 1924 farmers founded the “General Immigration League to bring in Poles for farm work”, before the State took over recruitment with the creation of the French National Office for Immigration in 1945.

The indispensability of foreign workers in agriculture was widely discussed in the spring of 2020 during the pandemic: “Delegating our food [...] to others is madness”, deplored the President, promising “revolutionary decisions” to “regain control” over the food sector.

This has not been the case. Behind the issuing of work and residence permits with no opposition to the employment situation, lies an extreme dependence on foreign labour, which is the front line of agricultural work and without which countries such as France, Italy, Spain, Germany, Belgium and the United Kingdom cannot ensure their food security.

Identity card of the article

| Original title: | Les oubliés de la crise agricole : pas de droit de séjour pour les saisonniers étrangers ? |

| Authors: | Gaeëlla Loiseau, Anne Lascaux, Béatrice Mésini |

| Publisher: | The Conversation France |

| Collection: | The Conversation France |

| License: | This article is republished from The Conversation France under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. An English version was created by Hancock & Hutton for Université Gustave Eiffel and was published by Reflexscience under the same license. |

| Date: | June 27, 2024 |

| Langages: | French and english |

| Keywords: | agriculture, immigration, professions, precarious employment, immigration law |

![[Translate to English:] Licence creative commons BY-SA 4.0 [Translate to English:] Licence creative commons BY-SA 4.0](https://reflexscience.univ-gustave-eiffel.fr/fileadmin/ReflexScience/Accueil/Logos/CCbySA.png)