How to republish

Read the original article and consult terms of republication.

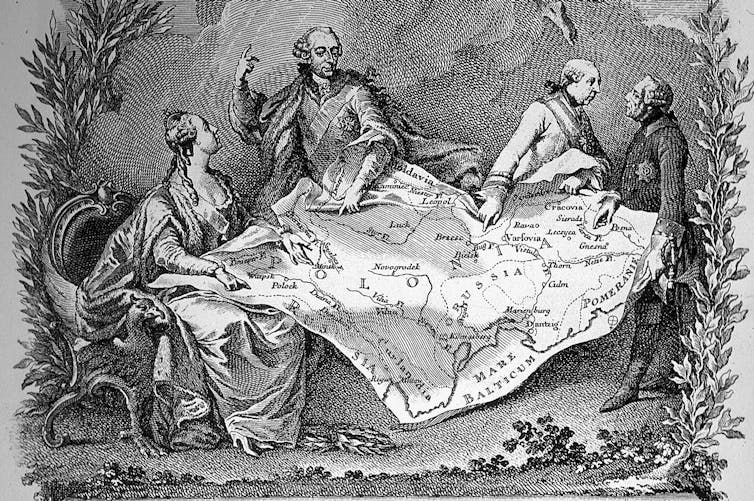

When Russia, Prussia and Austria partitioned Poland

In the current context of the war in Ukraine, with historic disputes between Warsaw and Moscow exacerbated, it is useful to look back on past events, which still remain very fresh in the Polish collective memory: the Third Partition of Poland, on 24 October 1795.

This was the day that the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, as established by the 1569 Union of Lublin, that united the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, was erased from the map. It was only following World War I that the two entities – Poland and Lithuania – would separately recover their independence.

A multicultural buffer space at the mercy of the nobility

In the mid 18th century, the fragility and potential collapse of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was a matter of concern for the great courts of Europe. At its height, the Commonwealth’s territory covered nearly a million km2, mainly made up of vast plains and dense forests. It was a buffer zone with no real natural borders, located between three powers that were hungry for expansion: Austria, Prussia and Russia.

Its population, estimated at over 11 million habitants, was ethnically, religiously and linguistically diverse, including Poles, Lithuanians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Tatars and Jews, as well as a number of Greek, Armenian and German communities. The majority of the population was rural and lived from agricultural activity - with the exception of Warsaw, Kraków and Lviv, large urban settlements were rare.

Poland-Lithuania was fundamentally aristocratic, dominated by the szlachta, the all-powerful Polish nobility. This aristocracy had control over all the country’s wealth, honours and political power, legitimated by an ideology based around the Sarmatians : the szlachta were said to be descended from the Scythian warrior people known as the Sarmatians, who remained undefeated by the Roman Empire.

This ideology nurtured a certain warmongering spirit, based on defending the glory of their valiant mythologised ancestors. It translated as arrogance towards foreigners and contempt towards peasants, as well as all those who work to support themselves in general.

Many fragile points and blockages

With regards to the economy, activity was greatly hampered by the deeply rooted system of serfdom and a chronic lack of investment in infrastructure. While their Austrian, Prussian and Russian neighbours had powerful governments capable of modernising their economies, the Polish ruling elite were not able to increase agricultural productivity and support the development of trade and manufacturing. Land was the property of the Crown (15%) and magnates from the high nobility (85%), but the majority of the szlachta were not landowners.

In Poland-Lithuania, the living conditions of the peasantry seemingly deteriorated in the first half of the 18th century, mainly due to increased statute labour. The country’s economy was mainly non-monetary in nature, with autarchic and gift-based practices common. Serfs consumed only a small amount of their production, while the magnates used their wealth to hold celebrations in order to curry favour with their large courts and granted offices to the poor nobles, to ensure their respective lifestyles.

As for legislation, Poland-Lithuania remained hampered by a large number of customs, to which the royal statutes and laws voted by the Sejm parliament were added. Despite multiple attempts at codification, the Commonwealth was not able to standardise its civil and criminal law. This led to a profoundly inegalitarian social order, which benefited the nobility and above all, the magnates. However, the second half of the 18th century was marked by several notable milestones: landowners lost the right to impose the death penalty on their serfs (1767) and the torture and trial of witches were outlawed (1776).

Politically, the hybrid regime, between an aristocratic republic and elective monarchy, was a source of major blockages and malfunctions. The aristocracy contributed to public affairs via assemblies of districts in charge of local affairs and the elections of deputies in the kingdom’s legislature – the Sejm – which was convened every two years. This central institution of the republic, consisting of the king and the two chambers (the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies), voted on laws and taxes, declared wars, signed treaties and appointed the monarch.

He shared his power with the rest of the Sejm, but carried out specific duties: proposing and approving laws, directing the army and diplomatic operations, naming individuals to public functions and convening assemblies. The king was counselled by ministers, which he appointed for life (marshals, generals, treasurers and chancellors) and which limited his authority, sometimes representing veritable powers of opposition. He also had to compromise with the Senate, made up of bishops and provincial administrators (voivodes and castellans), whose duty it was to advise and curb him.

However, the szlachta continued to expand their privileges and capabilities for action in public affairs, particularly by exercising legislative power through liberum veto. This was a process that required unanimity in votes in the Sejm, based on the principle that all nobles should have truly equal political rights. It meant that a single deputy could block a proposed law, or even force the entire assembly to separate by nullifying all decisions made in a session. Evidently, the repeated use of liberum veto paralysed the parliament’s work and subsequently, the functioning of institutions. This political system of aristocratic democracy de facto degenerated into an oligarchy run by a few major magnate families: the Czartoryski, the Potocki, the Radziwill, the Branacki, the Poniatowski, etc.

From a military point of view, Poland-Lithuania also suffered from structural limitations: the regular army was only 10,000-strong. Mass conscription of nobles was possible, but could be blocked by the use of liberum veto. The Polish army was therefore in no position to compete with its powerful neighbours’ large armies. Observers and travellers at the time generally remarked upon how backward and set in its ways the Commonwealth was in most areas.

Efforts at reform unsuccessful in preventing the country from being dismantled

On 6 September 1764, the Sejm elected Stanislas II Auguste Poniatowski (1732-1798) King of Poland and Grand-Duke of Lithuania, following the machinations of his former mistress, Empress of Russia Catherine II (1729-1796). From that point on, he was seen as a creature in the service of the Tsarina and his legitimacy was undermined. And yet, he was far from simply being a servile Russian agent. The learned prince wished to continue the Czartoryski reforms to make the Polish state more efficient, by replacing the existing regime, which was causing anarchy in the aristocratic republic, with a true monarchy.

Poland was one of the rare countries in Europe to practice true religious tolerance, though there were still legal inequalities between the various confessions. The “dissident” nobles (Protestant and Orthodox) sought to have the same rights as the Catholics. This demand served the interests of the Prussians (Protestant) and the Russians (Orthodox), who supported them. However, the Catholic nobles were against it, as, if these parties gained access to liberum veto, they would become dependent on the dissidents and therefore on Russia and Prussia.

In 1767, Nicolas Repnin (1734-1801), Russian ambassador to Warsaw, orchestrated manoeuvres in the Sejm to structure the conflict, going far beyond religion, by creating confederations. These confederations were legal, political associations whose aim was to create a union of nobles with the aim of defending the republic from internal or external danger. Repnin encouraged the creation of three confederations: the Sluck Confederation, for the Orthodox nobility, the Torún Confederations, for the Protestants, and the Radom Confederation, for the conservative Catholics who opposed Stanislas II’s reforms.

The formation of these groups led to an extraordinary Sejm session in 1767-1768 : during which equal rights were granted to non-Catholics and Catherine II was recognised as protector of “Polish freedoms”. On 24 February 1768, a treaty of friendship and perpetual guarantee was signed between Russia and Poland. The Tsarina committed to guaranteeing the Polish territory and political institutions - with this, the entire Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth came under the control of Russia.

In reaction to this de facto tutelage, a new confederation formed in Bar (29 February 1768) to defend their homeland and Catholic faith. The Bar Confederation was supported by France and the Ottoman Empire. It declared war on Russia (6 October 1768) following a massacre carried out by pro-Russians on its territory. The Polish insurrection turned into simultaneously a civil and an inter-state war.

This situation served Austrian and Prussian interests, as it contained Russian expansion. However, the military reverses piled up, both internally and externally. When the Confederation was finally defeated, the turmoil that it caused served as a pretext for the First Partition of the country through a treaty signed between Maria Theresa of Austria (1717-1780), Frederick II of Prussia (1712-1786) and Catherine II, on 5 August 1772. Meanwhile, the Bar Confederation sought support in France, but found that only intellectuals, such as Paul Pierre Lemercier de la Rivière (1719-1801), Gabriel Bonnot de Mably (1709-1785) and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) were willing to work – ultimately in vain - to achieve institutional reforms.

From partition to extinction

In the 1772 Partition, the Commonwealth lost a third of its territory and population. The Polish government in place, with Stanislas II still at the helm, had not given up on bringing reform to its institutions. During the “Great Sejm” of 1788-1792, a written constitution was drafted.

An Act of Government Act of Government (3 May 1791) established a hereditary monarchy, rather than an elective one, with the crown returning to the House of Saxony after Stanislas II’s death. The king had full executive power and presided over the “Guard of Laws”, assisted by the Primate, five ministers and two secretaries of state. Legislative power belonged to the permanent, bicameral Sejm (Chamber of Deputies and Senate). The Confederations and liberum veto were abolished. Local prerogative and that of the bourgeoisie were expanded.

Catherine II opposed these reforms, which supported the Commonwealth’s emancipation from Russia. A new Russo-Polish war began. Conservative magnates backed by Russia formed the Targowica Confederation. Under military pressure, the King was forced to join it and return to the former political order. Prussia, under Frederick William II (1744-1797), remained on the sidelines, but participated in another partition of Polish territory in January 1793 with Russia, though without Austria this time, which was occupied with war against revolutionary France. From that point, Poland was reduced to a country of around 200,000 km2 and 3 million inhabitants.

In response, General Tadeusz Kościuszko (1746-1817), veteran of the American War of Independence, organised and led a revolt to liberate Poland. He commanded the regular army and enlisted thousands of volunteer peasants. Though they had some initial success, Kościuszko was wounded and captured on 10 October 1794. The insurrection was then violently repressed by Russia, which organised a third and final partition of Poland, with Austria and Prussia once again, on 24 October 1795. Poland thus succumbed to the voracity of its powerful neighbours and the country was entirely wiped off the European map, until it was resurrected, at the same time as Lithuania, post-World War I in 1918.

Identity card of the article

| Original title: | Quand la Russie, la Prusse et l’Autriche se partageaient la Pologne |

| Authors: | Bernard Herencia and Thérence Carvalho |

| Publisher: | The Conversation France |

| Collection: | The Conversation France |

| License: | The original version of the article was published in French by The Conversation France under Creative Commons license. Read the original article. An English version was created by Hancock & Hutton for Université Gustave Eiffel and was published by Reflexscience under the same license. |

| Date: | September 1st, 2023 |

| Languages: | English (a French version is available) |

| Keywords: | history, Europe, Russia, Austria, Poland, Eastern Europe, Lithuania, political history |

![[Translate to English:] Licence creative commons BY-SA 4.0 [Translate to English:] Licence creative commons BY-SA 4.0](https://reflexscience.univ-gustave-eiffel.fr/fileadmin/ReflexScience/Accueil/Logos/CCbySA.png)